Executive Summary

The idea that humans have an immaterial soul, separate to the body, has spanned history and culture. This idea is known as dualism. The concept of the spirit is fundamental to the Christian church. Christians are usually taught that humans are a spirit, having a soul and living in a body (the Triune Being Hypothesis). The concept permeates the work of Dr Caroline Leaf, forming the basis for her assumptions that our minds can control matter.

However, the Bible does not state that the spirit and soul are separate to the body, only that they are linked in the earthly and supernatural realms. Over the last few decades, cognitive neuroscience has demonstrated that definable neural networks within the human brain mediate the components of the traditional soul. Religious belief and spiritual experiences are also heavily reliant on the human brain.

These findings, along with a number of other philosophical objections, prove that dualism is not compatible with science or philosophy. Dr Leaf’s reliance on the concept of dualism creates an intellectual dissonance between her teaching and neuroscience.

The notion that the soul and the spirit are separate to the body is also incorrect. However, quantum physics, and String Theory in particular, suggest that other dimensions and other universes exist, which may provide a scientifically plausible explanation of both natural and supernatural realms. It may be that our earthly body houses our natural spirit and soul within the brain, but that these are translocated to the celestial realm upon death. The challenge for the Christian church now is to unite the evidence of cognitive neuroscience with the description of the spirit, soul and body from scripture and further delineate the doctrine of humans as triune beings.

(Word count: 7256, including references)

Introduction

Are we a body with a mind, or a mind with a body?

It sounds a bit like the age-old chicken and the egg conundrum. In Ancient Greece, Plato proposed that human beings have an immaterial soul distinct from the material body while Descartes reinvigorated the idea in the 17th century. But the idea of the distinct immaterial soul is also found throughout different religions, and seems to be interwoven through the Bible as well.

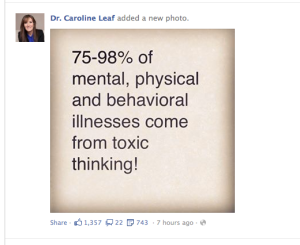

For Dr Caroline Leaf, Communication Pathologist and self-titled Cognitive Neuroscientist, dualism is fundamental to her theory of “Mind over Matter”. In her 2013 book, “Switch On Your Brain”, Dr Leaf states that, “Our mind is designed to control the body, of which the brain is a part, not the other way around. Matter does not control us; we control matter through our thinking and choosing.” [1: p33] She has also made several similar public statements via her social media feeds, such as, “Don’t blame your physical brain for your decisions and actions. You control your brain!” (6/6/2014) and “Your mind is all powerful! Your brain simply captures what your mind dictates! 2 Timothy 1:7.” (11/5/2014)

I have previously blogged about the scriptural and scientific voracity of Dr Leaf’s various statements on the Mind-Body problem (see also “Dr Caroline Leaf and the Myth of the Blameless Brain“, and others). But when she published, “Your mind will adjust your body’s biology and behaviour to fit with your beliefs” (21/6/2014) I thought enough was enough. The concept of dualism not only permeates the teachings of Dr Leaf, but also significantly influences the current understanding of the Biblical principles of the soul and spirit. So, this topic deserves an in-depth review, to ensure that the thinking within the church aligns with both scripture and science.

The Triune Being Hypothesis

On the 9th of June 2014, Dr Leaf published another meme on her social media feeds, “We are triune beings designed to be lead by the Holy Spirit … who speaks to our spirit. Our spirit controls our soul/mind and our soul/mind controls our body.”

By virtue of growing up in a Christian family, going to a Christian school, and digesting thousands of sermons during my lifetime, I’m very familiar with the concept of humans as a triune being (“triune”, meaning “three in one”). The concept I’ve been taught is similar to Dr Leaf’s view: that humans consist of three separate but interlinked components, the ethereal spirit and soul, and the physical body. The soul, in turn, consists of the mind, will and emotions. The three-part design reflects the image of God who is, of course, a triune being (the Holy Trinity: Father, Son and Holy Spirit). The hypothesis proposes that the body is just an earthly dwelling for a being that is fundamentally spirit in nature, the soul being the intermediary between the two.

In keeping with the theme, this essay will be in three parts! First, I review the Biblical evidence relating to the body, soul and spirit. Second, I review the scientific evidence relating to the spirit and soul. And finally, I discuss how the scriptural and scientific evidence relates to our current understanding of dualism, the triune being hypothesis and the implications for Dr Leaf and Christianity more broadly.

The Bible on the Triune Being Hypothesis

One of the fundamental arguments used by those who support the idea of man as a triune being is the way the Apostle Paul used distinct words to describe body, soul and spirit within the same sentence. For example, in 1 Thessalonians 5:23, Paul wrote, “And the very God of peace sanctify you wholly; and I pray God your whole spirit and soul and body be preserved blameless unto the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ” (emphasis added).

The three words used in ancient Greek were pneuma (‘spirit’), psyche (‘soul’) and soma (‘body’). According to Thayer’s Greek Lexicon, the words pneuma (‘spirit’) and psyche (‘soul’) were often used indiscriminately. So although the Apostle Paul distinctly used the word pneuma separately to the word psyche as in 1 Thessalonians 5:23, most of the other New Testament writers weren’t so precise.

James wrote that without the spirit (pneuma), the body (soma) would die (James 2:26). This also suggests that the spirit is different to the body, but still integral to the whole person, although given the interchangeable use of the terms, James may have also been referring to the soul.

However, Jesus told the disciples in Matthew 10:28, “And fear not them which kill the body (soma), but are not able to kill the soul (psyche): but rather fear him which is able to destroy both soul (psyche) and body (soma) in hell.” This suggests that both the soul and the body maybe found in hell, a post-death spiritual dimension (see also Luke 12:5). So it seems that at least in some form, our supernatural selves also possess a body and mind.

This idea seems to have some backing in the form of the description given in the Bible of the resurrected body of Jesus. After Jesus was crucified and buried, scripture describes the empty tomb, and the multiple sightings of Jesus by the disciples up until the time that he ascended into heaven (Luke 24). He walked along the road to Emmaus with two disciples, Cleopas and probably Cleopas’ wife Mary (see also John 19:25). He then appeared in the middle of the group of disciples within an instant. He still possessed the defects caused by the crucifixion. He ate some broiled fish and some honeycomb (see Luke 24:42-43). He said to the disciples at this meeting with them, “Behold my hands and my feet, that it is I myself: handle me, and see; for a spirit hath not flesh and bones, as ye see me have.” (Luke 24:39) Not only did he have the same physical characteristics as his pre-resurrected body (same appearance, same gender etc), but he also had similar mental traits, such as self-awareness, memory of his pre-resurrection life, and emotions and connection to the people around him. However, he was not subject to the natural laws of physics, twice suddenly appearing in a closed room (John 20:19 and 26).

Therefore it appears that rather than being a spirit housed in a body and furnished with a soul, we are instead an inseparable combination of body, soul and spirit – three unique but indivisible parts – but in different dimensions depending on which side of eternity we currently reside.

1 Thessalonians 5:23 confirms, rather than precludes, this view. Reviewing the scripture again, Paul wrote, “And the very God of peace sanctify you wholly; and I pray God your whole spirit and soul and body be preserved blameless unto the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ.” Paul chooses to emphasize all three components of our triune being equally in his prayers and wishes. If only our spirit was to pass into the celestial realm, then Paul wouldn’t have needed to delineate the three parts of our triune composition, but could have instead written “And the very God of peace sanctify you wholly; and I pray God your whole spirit be preserved blameless unto the coming of our Lord Jesus Christ”. By penning, “whole spirit and soul and body be preserved blameless”, Paul seems to treat all three parts as equally important to our future with Christ.

It follows that if we believe that our heavenly body is an integral part with our spirit and soul on the celestial side of eternity, then it should follow that our spirit and our soul are part of, and dependent on, our earthly body on this side of eternity.

This proposal differs from the conventional wisdom at two fundamental points:

1. I suggest that the spirit is integral to, and dependent on our earthly body whilst we live on the earth,

and

2. I suggest that the whole person is translated across from the earthly realm to the celestial, rather than just the spirit.

Such suggestions are compatible with current scientific understanding. There is ample evidence of spiritual neural networks that complement the emotional and moral parts of our brain (this will be discussed further in a future section).

String Theory provides a plausible explanation of other dimensions and worlds in parallel with our own which could very easily explain a spiritual dimension. String Theory is the theory that the very fabric of the cosmos is made up of tiny vibrating loops of energy, which physicists call “strings”. These strings are almost impossibly small. Physicist Brian Greene said that, “Each of these strings is unimaginably small. In fact, if an atom were enlarged to the size of the solar system, a string would only be as large as a tree!” [2] It’s the shape and vibrational pattern of each of these strings that gives subatomic particles their properties, which in turn combine to make up everything we see in the universe, including ourselves.

In order for these strings to vibrate and move the way they are predicted to, String Theory postulates that there are actually 11 dimensions of space. In one of these dimensions, a string could become stretched out into a membrane, or a “brane” for short. I’ll let Brian Greene and colleagues explain it further.

“BRIAN GREENE: The existence of giant membranes and extra dimensions would open up a startling new possibility, that our whole universe is living on a membrane, inside a much larger, higher dimensional space. It’s almost as if we were living inside … a loaf of bread? Our universe might be like a slice of bread, just one slice, in a much larger loaf that physicists sometimes call the “bulk.” And if these ideas are right, the bulk may have other slices, other universes, that are right next to ours, in effect, “parallel” universes. Not only would our universe be nothing special, but we could have a lot of neighbours. Some of them could resemble our universe, they might have matter and planets and, who knows, maybe even beings of a sort. Others certainly would be a lot stranger. They might be ruled by completely different laws of physics. Now, all of these other universes would exist within the extra dimensions of M-theory, dimensions that are all around us. Some even say they might be right next to us, less than a millimetre away. But if that’s true, why can’t I see them or touch them?

BURT OVRUT: If you have a brane living in a higher dimensional space, and your particles, your atoms, cannot get off the brane, it’s like trying to reach out, but you can’t touch anything. It might as well be on the other end of the universe.

JOSEPH LYKKEN: It’s a very powerful idea because if it’s right it means that our whole picture of the universe is clouded by the fact that we’re trapped on just a tiny slice of the higher dimensional universe.” [3]

Although it sounds preposterous, String Theory isn’t a fantasy of a few physicists who have watched too many sci-fi shows. String Theory is mathematically proven, and accepted by the majority of scientists.

What if our physical reality was one brane, the supernatural realm was a different brane, and heaven was another? Angels could be all around us, in a different dimension of space that we cannot ordinarily perceive, but who have the ability to move into our dimension if required. When we die, it’s possible that our whole person is transformed into a different dimension – the supernatural or celestial brane. The physical body remains like a snakeskin left after the snake has shed it.

My theory is only one of many possible theories. Ultimately, they all remain scientifically unprovable. While String Theory is well accepted by physicists all over the world, and the predictions of extra dimensions and branes are mathematically robust, my hypothesis that the supernatural realm is a dimension of space on a brane is conjecture, and would be impossible to test mathematically or scientifically. The concept of extra dimensions and branes is one way of explaining the Bible’s description that our spirit, soul and body remain together, but in a different realm to the physical reality that we currently experience.

Science on the Triune Being Hypothesis

So if it’s possible that we can live as a whole person, spirit, soul and body, in a celestial dimension, what makes up our spirit, soul and body in the physical dimension?

Biological science and neuroscience have uncovered many of the previously mysterious qualities that define us as human beings, although there is still much more to be uncovered.

- THE BODY

The body is our physical selves – our flesh and blood, sealed by our coating of skin. The body is so ultimately universal, I don’t want to waste space justifying the case for the normal. The obvious physical separation makes each person easy to delineate, although there are rare exceptions that challenge the division of body and soul/spirit.

In May 2014, Faith and Hope Howie were born in Sydney (Australia) [4]. They were born with two separate faces and two brains which merged into one brain stem. They had one body. While they were considered to be conjoined twins, in the strictest medical sense, they had a condition called disrosopus, resulting from the over-expression of a protein involved in the formation of the cranial structures [5]. The condition is extremely rare, and most children with the condition are either stillborn, or don’t survive for more than 24 hours after birth. That Faith and Hope survived for 19 days is a miracle in itself.

Strictly speaking, Faith and Hope were one baby that developed two brains, rather than being twins who failed to adequately separate. So did they have two souls or one? I don’t propose to answer this question here, but it will be worth pondering as we review the concept of the soul.

- THE SOUL

The soul is traditionally considered to consist of the mind, will and emotions. In the earthly realm, there is overwhelming evidence that all the parts of the traditional soul are found in the human brain.

a. The Mind

The mind is considered to be “a person’s ability to think and reason; the intellect.” [6] As we will discuss in more detail later, dualism suggests that the mind is an ethereal force separate to the body. But modern neuroscience has accumulated decades of evidence to the contrary. Our stream of consciousness is linked to the function of our working memory [7, 8]. Working memory in turn is heavily dependent on the part of the brain called the pre-frontal cortex and on a neurotransmitter called dopamine [9]. When dopamine-secreting nerve cells are damaged in the pre-frontal cortex, conditions involving disordered thought such as schizophrenia occur [9, 10]. Schizophrenia is best known for hallucinations, essentially hearing and/or seeing things that are not there. These symptoms are reversed by medications that enhance the dopamine response [11]. Lesions of the frontal lobe can also result in the loss of abstract thinking [9]. So it is fair to say that the function of the mind is dependent on the brain, specifically the pre-frontal cortex. If the function of the pre-frontal cortex is disrupted, either by damage to a group of cells, or by impairment of the signaling of those cells via disruption of the neurotransmitter dopamine, the patterns of thought change. These changes in the patterns of thought can be reversed if the impairment can be reversed. Therefore the mind is dependent on the brain. If the mind were independent of the brain, then the function of the mind would not be affected by damage or impairment to the physical brain.

Our stream of thought is a function of our working memory utilizing a wider area of the brains cortex to better process important information. Baars [7, 12] noted that the conscious broadcast comes into working memory which then engages a wider area of the cerebral cortex necessary to most efficiently process the information signal.

We perceive thought most commonly as either pictures or sounds in our head (“the inner monologue”), which corresponds to the slave systems of working memory. When you “see” an image in your mind, that’s the visuospatial sketchpad. When you listen to your inner monologue, that’s your phonological loop. When a song gets stuck in your head, that’s your phonological loop as well, but on repeat mode.

There is another slave system that Baddeley included in his model of working memory called the episodic buffer, “which binds together complex information from multiple sources and modalities. Together with the ability to create and manipulate novel representations, it creates a mental modeling space that enables the consideration of possible outcomes, hence providing the basis for planning future action.” [13]

Deep thinking is a projection from your brains executive systems (attention or the default mode network) to the central executive of working memory, which then recalls the relevant information from long-term memory and directs the information through the various parts of the slave systems of working memory to process the complex details involved. For example, visualizing a complex scene of a mountain stream in your mind would involve the executive brain directing the central executive of working memory to recall information about mountains and streams and associated details, and project them into the visuospatial sketchpad and phonological loop and combine them via the episodic buffer. The episodic buffer could also manipulate the scene if required to create plans, or think about the scene in new or unexpected ways (like imagining an elephant riding a bicycle along the riverbank).

Even though the scene appears as one continuous episode, it is actually broken up into multiple cognitive cycles, in the same way that images in a movie appear to be moving, but are really just multiple still frames played in sequence.

So our mind, also called our stream of thought, is simply a projection of information from our working memory, broadcast to our cerebral cortex, and our consciousness, for extra processing power. It is dependent on our pre-frontal cortex. When the pre-frontal cortex is damaged, our mind can experience defective output, as is the case in thought disorders such as schizophrenia.

b. The Will

The second part of our soul is our will, “the faculty by which a person decides on and initiates action.” [6] Like our mind, the feeling that we have free will is a ubiquitous human trait. Haggard observed, “Most adult humans have a strong feeling of voluntary control over their actions, and of acting ‘as they choose’. The capacity for voluntary action is so fundamental to our existence that social constraints on it, such as imprisonment and prohibition of certain actions, are carefully justified and heavily regulated.” [14]

Again, like the mind, our feeling of our will comes from our brain. Over three decades ago, Libet performed an experiment that demonstrated measurable neural activity occurring up to a full second before a test subject was consciously aware of the intention to act [15]. More recently, a study by Soon et al showed that predictable brain activity occurred up to eight seconds before a person was aware of their intention to act [16]. Haggard again, “Modern neuroscience rejects the traditional dualist view of volition as a causal chain from the conscious mind or ‘soul’ to the brain and body. Rather, volition involves brain networks making a series of complex, open decisions between alternative actions.” [14]

These brain networks initially involve the basal ganglia deep in the brain along with the dopamine rewards system, which provide a flexible interaction between the person’s current situation and the memory of previous similar situations. Also important are the frontal lobes in general, and the pre-Supplementary Motor Area (pre-SMA) in particular, which have crucial roles in keeping actions focused and ‘on task’, or in “binding intention and action”. Parts of the pre-SMA are also active in voluntary selection between alternative tasks and in switching between the selections. An area of the anterior frontomedian cortex, near the pre-SMA, was activated in veto trials more than in trials on which participants made an action. This brain activity might have a key role in self-control [14].

Damage to different areas of the frontal cortex and the other parts of the motor system can result in a number of different conditions, highlighting the role of the brain in our “voluntary” actions. For example, blockage of a small artery in the brain called the artery of Huebner may cause a stroke of the head of the Caudate Nucleus, resulting in the loss of voluntary movement, loss of motivation and loss of speech [17]. Psychosis and ADHD are also disorders of action output of the brain, both of which improve with medications that improve the function of the frontal lobes of the brain. In children with ADHD, the change can be dramatic in a short space of time, and research across the last few decades proves the effect is more than placebo [18, 19].

The feelings of intention and the sense of agency (planning to do or being about to do something, and the sense that one’s action has indeed caused a particular external event) are so fundamental to human experience that it’s hard to consider the alternative: that our ‘free will’ is by-and-large an illusion. Our brain has already reviewed a number of alternative actions for any particular situation, and by the time that our consciousness becomes aware of the decision our brain has made, our motor area of our brain has already primed the neuromuscular circuit in preparation to perform the action. At best, our ‘free will’ is more like a veto function rather than a full conscious control of our behaviour [20]. Multiple parts of our brain are involved in the planning and execution of our actions, especially the basal ganglia and the pre-SMA.

c. The Emotions

Emotions are a difficult concept to define. Despite being studied as a concept for more than a century, the definition of what constitutes an emotion remains elusive. Some academics and researchers believe that the term is so ambiguous that it’s useless to science and should be discarded [21]. I use a concept of emotions described by Dr Alan Watkins [22], which thinks of our emotional state as the sum total of the state of our different physiological systems, while feelings are the awareness, or the perception of our emotional state. However, I should stress that this is only one concept. Often the terms “emotion” and “feelings” are used interchangeably.

That said, neurobiology has still mapped specific feelings/emotions to different parts of the brain. The amygdala is often considered the seat of our fears, the anterior insula is responsible for the feeling of disgust, and the orbitofrontal and anterior cingulate cortex are involved in a broad range of different emotions [23].

Different moods have been linked to specific neurotransmitter systems in the physical brain. A predisposition to anxiety is often linked to variations in the genes for serotonin transport [24] while positive and negative affect (“joy / sadness”) are linked to the dopaminergic system [25].

What is clear is that scientifically speaking, our emotions and the perception of them is dependent on our physical brain.

Summarizing the Soul

Dualism’s view that the soul is an ethereal force separate to the body is redundant. The evidence from the scientific study of the brain makes it clear that every aspect of the traditional ‘soul’ – the mind, will and emotions – is housed in the brain.

3. THE SPIRIT

The scientific study of spirituality is on the leading edge of scientific progress.

Whether a spiritual realm exists is not something that can be tested scientifically. I’ve discussed the Biblical view of the triune being hypothesis earlier in this essay, and suggested that a spiritual realm is at least scientifically plausible depending on your interpretation of String Theory. Ultimately, it remains a matter of faith.

The existence of the spiritual realm may be debatable, but what’s well accepted is that human beings are fundamentally spiritual. Spiritual or mystical experiences are reported across all cultures [26], and throughout history, religions in various forms have spanned the globe, integral to civilizations and the forming of cultural identity. It’s therefore not surprising to find that the brain is a focal point for spiritual experience. Just as hunger, laughter, anger and many other characteristic human traits have their own unique pathways in the brain, so does the experience of the divine.

Spirituality can be defined as “an individual’s experience of and relationship with a fundamental, nonmaterial aspect of the universe that may be referred to in many ways – God, Higher Power, the Force, Mystery and the Transcendent and forms the way by which an individual finds meaning and relates to life, the universe and everything.” [27] On consideration, spirituality encompasses both episodic mystical experiences and ongoing religious beliefs.

Spiritual experiences involve multiple brain regions, and are mediated by a number of different neurotransmitters. In a study of Carmelite Nuns reliving a spiritual experience, Beauregard and Paquette observed activation of the right medial orbitofrontal cortex, the right medial prefrontal cortex, the right dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, the right middle temporal cortex and the left superior and inferior parietal lobes [26]. There is also evidence that dopamine and serotonin are important neurotransmitters in the religious experience [27]. More recent work on the function and connectivity of the medial orbitofrontal cortex shows all of these brain regions have strong connections to each other [28], and that together they function to encode and determine the predicted and real values of our choices. In particular, the medial orbitofrontal cortex helps to encode the anticipated rewards of incoming stimuli. The anticipated and actual values for the perceived stimuli are compared to give a prediction error, which serves as a teaching signal that can be used to improve future value assignments at the time of decision-making [29]. This is intrinsically linked to the limbic rewards system via dopamine, which partially explains the increase in dopamine during intense religious experiences.

Yet spiritual experiences are more than the rewards processing of incoming stimuli. Intense religious experiences have been reported during the aura of temporal lobe epilepsy, especially on the right side [27, 30]. It maybe that the right temporal lobe is largely responsible for the sensed presence of a higher being, and for the more intense religious experiences. Some scientists even went so far as to claim that complex weak magnetic stimulation of the right temporal cortex produced intense religious experiences [31], although this maybe more related to the suggestibility of the subjects rather than the temporal lobe “stimulation” [32]. Therefore, while it is likely that the right temporal lobe is involved in experiences of spirituality, there is no lab-based repeatable evidence to confirm or delineate it.

However, the cognitive and neuroanatomical correlates of religious belief have been delineated. Kapogiannis and colleagues summarized their work by stating that, “religious belief engages well-known brain networks performing abstract semantic processing, imagery, and intent-related and emotional theory of mind, processes known to occur at both implicit and explicit levels. Moreover, the process of adopting religious beliefs depends on cognitive-emotional interactions within the anterior insulae, particularly among religious subjects. The findings support the view that religiosity is integrated in cognitive processes and brain networks used in social cognition, rather than being sui generis.” [33]

If spirituality is indeed solely based on the structure and function of the human brain, what are the implications for organized religion?

To start with, it would mean that those with deficits in certain cognitive functions would experience spirituality to a lesser degree, or at least experience it to a different degree. In keeping with this hypothesis, Canadian researchers have shown that those people with mentalization deficits (reduction in the ability to understand the mental state of oneself and others which underlies overt behaviour), such as people on the Autism spectrum, are less likely to believe in a personal God [34]. On the flipside, other people would be naturally wired to the divine: intuitive and sensitive to the experience of the spiritual.

Moreover, even if a person is not naturally spiritual, one can train oneself to become more spiritual. The brain increases the neural connections within regions that are recurrently stimulated, which leads to expertise. For example, the mid-posterior hippocampus of London taxi drivers is much larger compared to London bus drivers. London taxi drivers are required to drive anywhere in London without maps, and so develop a much larger region of spatial knowledge than the bus drivers, who drive pre-determined routes [35]. Similarly, novices who meditate show increased growth of neural networks involved in the regulation of emotion [36]. It would follow that brain regions involved in the processing of spiritual experience would increase with regular spiritual practice, resulting in a greater sense of the presence of God and his joy.

On the other hand, if acceptance of God is dependent on the function of certain networks within our brain, then how does that affect the foundational principle of salvation? Is it justice if one is condemned to eternal damnation when one has less capacity to believe in the first place?

I cannot offer a definitive answer to that question. Maybe there is no definitive answer? Given that Jesus told Nicodemus, “For God sent not his Son into the world to condemn the world; but that the world through him might be saved” (John 3:17), and that Peter says about God, “The Lord is not slow in keeping his promise, as some understand slowness. Instead he is patient with you, not wanting anyone to perish, but everyone to come to repentance” (2 Peter 3:9), I trust that God will judge everyone fairly, but I’m not sure how the capacity of a person to accept salvation is judged. Perhaps that’s something that someone who’s theologically trained can comment on.

The Triune Being Hypothesis – A New Approach

In summary, while the Bible makes a distinction between body, soul and spirit, it maintains that they are inseparable parts of the same whole person. In the earthly realm, our spirit and the various aspects that traditionally constitute our soul are all enabled though various networks within our physical brain. The Bible also offers evidence that in the transition from the terrestrial to the celestial dimensions, the whole person is translocated and transformed, not just the spirit or soul. Like a reptile shedding its skin, our earthly body and brain remain after death but the person has been translocated into the celestial realm.

Dualism

Psychoneural or Cartesian dualism is the premise that matter and mind are distinct entities or substances; that the one can exist without the other; and that they may interact, but that neither can help explain the other.

Dualism appears self-evident. It seems to explain behavior; and it accounts for the survival of the soul after death. Our mind and our body also appear separate. We have direct knowledge of our mental states, but we do not have direct knowledge of our brain states, so by simple logic, our mental states are not identical with our brain states. Dualism seems to be the obvious model of choice.

Despite claiming to be a cognitive neuroscientist, Dr Leaf embraces dualism, expanding the original concept of a soul into the broader idea of the soul and spirit of the triune being hypothesis, complete with its own hierarchy, “We are triune beings designed to be lead by the Holy Spirit … who speaks to our spirit. Our spirit controls our soul/mind and our soul/mind controls our body.” (Dr Leaf social media post, 9/6/2014)

However, we know that executive functions, emotions and even spiritual experiences can be induced or improved by stimulating the responsible brain networks (electrically in the lab, or with medications). And pathological changes to the brain, such as tumours, strokes, or brain injuries, all have the capacity to change the emotional or cognitive function of the sufferer, depending on the location of the lesion within the brain. If the mind were truly separate to the brain, then changes to the physical brain would not influence the mind or soul. Therefore, medicine and cognitive neuroscience have shown that dualism is false.

Philosophically, dualism is also fatally flawed. According to Bunge [37], dualism fails on a number of counts:

1. Dualism is conceptually fuzzy: “the expression ‘mind-body interaction’ is an oxymoron because, by hypothesis, the immaterial mind is impregnable to physical stimuli, just as matter cannot be directly affected by thoughts or emotions. The very concept of an action is well defined only with reference to material things.”

2. Dualism is experimentally irrefutable: “since one cannot manipulate a nonmaterial thing, as the soul or mind is assumed to be, with material implements, such as lancets and pills.”

3. Dualism considers only the adult mind: “Hence it is inconsistent with developmental psychology, which shows how cognitive, emotional and social abilities develop (grow and decay) along with the brain and the individual’s social context.”

4. Dualism is inconsistent with cognitive ethology: “in particular primatology … comparative psychology and cognitive archaeology”.

5. Dualism violates physics: “in particular the law of conservation of energy. For instance, energy would be created if a decision to take a walk were an event in the nonmaterial soul. Moreover, dualism is inconsistent with the naturalistic ontology that underpins all of the factual sciences.”

6. Dualism confuses even investigators who are contributing to its demise: “in the cognitive, affective and social neuroscience literature one often reads sentences of the forms ‘N is the neural substratum (or correlate) of mental function M,’ and ‘Organ O subserves (or mediates, or instantiates) mental function M’ – as if functions were accidentally attached to organs, or were even prior to them, and organs were means in the service of functions … Why not say simply that the brain feels, emotes, cognizes, intends, plans, wills, and so on? Talk of substratum, correlate, subservience and mediation is just a relic of dualism, and it fosters the idea (functionalism) that what matters is function, which can be studied independently of stuff. But there is neither walking without legs nor breathing without lungs. In general, there is neither function without organ nor organ without functions.”

7. Dualism isolates psychology from most other disciplines: “insofar as none of them admits the stuff/function dichotomy.”

8. Dualism is barren at best, and counterproductive at worst, “In fact, it has spawn superstitions and pseudosciences galore … (and) has slowed down the progress of all the disciplines dealing with the mind.”

Bunge sums up the concept of dualism, “In short, psychoneural dualism is scientifically and philosophically untenable. Worse, it continues to be a major obstacle to the scientific investigation of the mind, as well as to the medical treatment of mental disorders.”

In short, dualism is dead.

Dualism and Dr Leaf

This damning evaluation of dualism poses significant ongoing problems for Dr Leaf and her teaching. Her proposition that “Our spirit controls our soul/mind and our soul/mind controls our body” is not supported by either science or by scripture. This significantly weakens her standing as a biblical and scientific authority, and highlights an intellectual dissonance between science, scripture, and her published work.

Unless Dr Leaf is prepared to review her position and change her teaching on the subject, the gap between her teaching and the accepted scientific position will only continue to widen, and her authority and respect will continue to weaken.

The New Triune Being Hypothesis and the Christian Church

For the Christian church, the Triune Being Hypothesis in its current form is now redundant. The review of the biblical evidence, and the current evidence from neuroscience, has disproven the triune being hypothesis insofar as there is no Biblical or scientific proof that the spirit, soul and body are separate entities. However, it’s reasonable to consider the spirit, soul and body as inseparable parts of the whole being, which are translocated together into the celestial realm upon death.

At the very least, the position of the Christian church on the nature of the soul/spirit requires review, and topic should be brought back to the table to be appropriately debated. It’s clear that the old, generally accepted hypothesis of the separate, immaterial soul/spirit is untenable with current scientific evidence. In this essay, I have proposed one theory which is at least plausible with current scientific understanding. However, there are many other theories that may be just as valid, and warrant consideration.

It’s my hope that with academic honesty and divine guidance, the truth of our triune nature can be further delineated.

References

- Leaf, C.M., Switch On Your Brain : The Key to Peak Happiness, Thinking, and Health. 2013, Baker Books, Grand Rapids, Michigan:

- Greene, B. The Elegant Universe: Part 2. [Transcript] 2003 [cited 2013, November 4]; Available from: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/physics/elegant-universe.html – elegant-universe-string.

- Greene, B. The Elegant Universe: Part 3. [Transcript] 2003 [cited 2014, June 28]; Available from: http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/physics/elegant-universe.html – elegant-universe-dimensions.

- Lyons, K. and Mills, D., ‘Gone to play with the angels’: Conjoined twins Faith and Hope are laid to rest after family’s tearful memorial service in Sydney. Daily Mail, UK, 2014 June 2 http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2645824/Gone-play-angels-Faith-trying-attention-Hope-happy-just-hold-finger-rest-Family-conjoined-twins-pay-tearful-tributes-Sydney-memorial-service.html

- Zaghloul, N.A. and Brugmann, S.A., The emerging face of primary cilia. Genesis, 2011. 49(4): 231-46 doi: 10.1002/dvg.20728

- Oxford Dictionary of English – 3rd Edition, 2010, Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK.

- Baars, B.J. and Franklin, S., How conscious experience and working memory interact. Trends Cogn Sci, 2003. 7(4): 166-72 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12691765 ; http://bit.ly/1a3ytQT

- Franklin, S., et al., Conceptual Commitments of the LIDA Model of Cognition. Journal of Artificial General Intelligence, 2013. 4(2): 1-22

- Arnsten, A.F., The neurobiology of thought: the groundbreaking discoveries of Patricia Goldman-Rakic 1937-2003. Cereb Cortex, 2013. 23(10): 2269-81 doi: 10.1093/cercor/bht195

- Goghari, V.M., et al., The functional neuroanatomy of symptom dimensions in schizophrenia: a qualitative and quantitative review of a persistent question. Neurosci Biobehav Rev, 2010. 34(3): 468-86 doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2009.09.004

- Melnik, T., et al., Efficacy and safety of atypical antipsychotic drugs (quetiapine, risperidone, aripiprazole and paliperidone) compared with placebo or typical antipsychotic drugs for treating refractory schizophrenia: overview of systematic reviews. Sao Paulo Medical Journal, 2010. 128: 141-66 http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1516-31802010000300007&nrm=iso

- Baars, B.J., Global workspace theory of consciousness: toward a cognitive neuroscience of human experience. Progress in brain research, 2005. 150: 45-53

- Repovs, G. and Baddeley, A., The multi-component model of working memory: explorations in experimental cognitive psychology. Neuroscience, 2006. 139(1): 5-21 doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.12.061

- Haggard, P., Human volition: towards a neuroscience of will. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2008. 9(12): 934-46 doi: 10.1038/nrn2497

- Libet, B., et al., Time of conscious intention to act in relation to onset of cerebral activity (readiness-potential). The unconscious initiation of a freely voluntary act. Brain, 1983. 106 (Pt 3): 623-42 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/6640273

- Soon, C.S., et al., Unconscious determinants of free decisions in the human brain. Nat Neurosci, 2008. 11(5): 543-5 doi: 10.1038/nn.2112

- Espay, A.J. Frontal Lobe Syndromes. Medscape eMedicine 2012 [cited 2014, July 1]; Available from: http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1135866-clinical – showall.

- Castells, X., et al., Amphetamines for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev, 2011(6): CD007813 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007813.pub2

- Hodgkins, P., et al., The Pharmacology and Clinical Outcomes of Amphetamines to Treat ADHD. CNS drugs, 2012. 26(3): 245-68

- Bonn, G.B., Re-conceptualizing free will for the 21st century: acting independently with a limited role for consciousness. Front Psychol, 2013. 4: 920 doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00920

- Dixon, T., “Emotion”: The History of a Keyword in Crisis. Emot Rev, 2012. 4(4): 338-44 doi: 10.1177/1754073912445814

- Watkins, A. Being brilliant every single day – Part 1. 2012 [cited 2 March 2012]; Available from: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q06YIWCR2Js.

- Tamietto, M. and de Gelder, B., Neural bases of the non-conscious perception of emotional signals. Nat Rev Neurosci, 2010. 11(10): 697-709 doi: 10.1038/nrn2889

- Caspi, A., et al., Genetic sensitivity to the environment: the case of the serotonin transporter gene and its implications for studying complex diseases and traits. Am J Psychiatry, 2010. 167(5): 509-27 doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2010.09101452

- Felten, A., et al., Genetically determined dopamine availability predicts disposition for depression. Brain Behav, 2011. 1(2): 109-18 doi: 10.1002/brb3.20

- Beauregard, M. and Paquette, V., Neural correlates of a mystical experience in Carmelite nuns. Neurosci Lett, 2006. 405(3): 186-90 doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2006.06.060

- Mohandas, E., Neurobiology of spirituality. Mens Sana Monogr, 2008. 6(1): 63-80 doi: 10.4103/0973-1229.33001

- Kahnt, T., et al., Connectivity-based parcellation of the human orbitofrontal cortex. J Neurosci, 2012. 32(18): 6240-50 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0257-12.2012

- Plassmann, H., et al., Appetitive and aversive goal values are encoded in the medial orbitofrontal cortex at the time of decision making. J Neurosci, 2010. 30(32): 10799-808 doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0788-10.2010

- Devinsky, O. and Lai, G., Spirituality and religion in epilepsy. Epilepsy Behav, 2008. 12(4): 636-43 doi: 10.1016/j.yebeh.2007.11.011

- Persinger, M.A., et al., The electromagnetic induction of mystical and altered states within the laboratory. Journal of Consciousness Exploration & Research, 2010. 1(7)

- Granqvist, P., et al., Sensed presence and mystical experiences are predicted by suggestibility, not by the application of transcranial weak complex magnetic fields. Neurosci Lett, 2005. 379(1): 1-6 http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/15849873

- Kapogiannis, D., et al., Cognitive and neural foundations of religious belief. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 2009. 106(12): 4876-81 doi: 10.1073/pnas.0811717106

- Norenzayan, A., et al., Mentalizing deficits constrain belief in a personal God. PLoS One, 2012. 7(5): e36880 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036880

- Maguire, E.A., et al., London taxi drivers and bus drivers: a structural MRI and neuropsychological analysis. Hippocampus, 2006. 16(12): 1091-101 doi: 10.1002/hipo.20233

- Holzel, B.K., et al., Mindfulness practice leads to increases in regional brain gray matter density. Psychiatry Res, 2011. 191(1): 36-43 doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2010.08.006

- Bunge, M., The Mind-Body Problem, in Matter and Mind. 2010, Springer Netherlands. p. 143-57.

Postscript: There is a lot more to String Theory, and anyone interested in knowing more would be well served by reviewing the transcripts or watching the PBS series “The Elegant Universe”, hosted by Brian Greene.